Just after the end of the American Revolution, before even the founding of Allegheny County, a time when Pittsburgh was more a fort than a town, a Lenape Indian named Mamachtaga (also Mamachtaguin) stabbed to death two white settlers, John Smith and Benjamin Jones, and injured two others, William Evans and William Freeman.

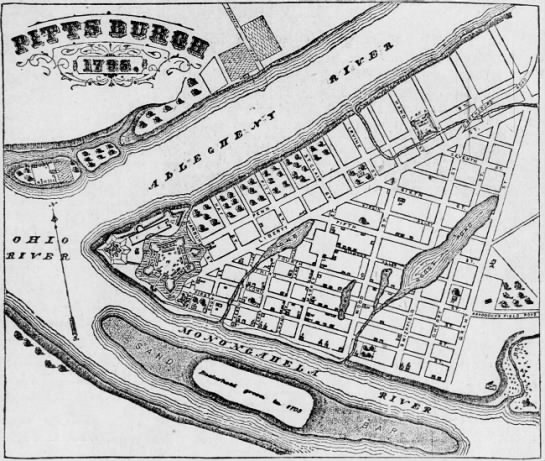

The killings, which occurred on May 11, 1785, on Killbuck Island, a now-vanished narrow strip of land just off the north shore of the Allegheny River across from the Point, were in reprisal for earlier attacks against his settlement by whites moving in to the area.

Tensions between Native Americans and white settlers had been intensified by the terms of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, signed months earlier, which forced the Lenape to cede the lands north of the Ohio River. To the Lenapes, who had been forced westward by European settlement of the mid-Atlantic coast over the previous century, the cycle of European incursion, conflict, treaty, and abrogration was a continuing betrayal.

After Mamachtaga was captured, he was held briefly at Fort Pitt, where threats were made to seize him from military control and kill him summarily. He was then transferred to Hannastown, a town that was founded as the Westmoreland County seat in 1773 but had since been destroyed by fire by the retreating British in 1782. All but the courthouse had been abandoned for the new county seat in nearby Greensburg. Two judges traveled from Philadelphia to preside at the trial.

Mamachtaga was represented by Hugh Henry Brackenridge, the most prominent Pittsburgher of the era, the founder of the Pittsburgh Gazette, the city’s first newspaper, the Pittsburgh Academy, which would become the University of Pittsburgh, and a future justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Brackenridge’s involvement in the case caused resentment among white residents. His chronicle of the case is the primary source of our understanding of it.

Brackenridge describes Mamachtaga as tempermental, violent, and prone to excessive drinking, a characterization that matches the stereotype of Native Americans a bit too closely to be entirely persuasive. He also states that Mamachtaga insisted on pleading guilty, characterizing him with a child-like honesty.

Despite the quality of his counsel and the significant due process protections he received under the circumstances, there was little chance Mamachtaga would not be convicted in a time and place so hostile to Native Americans. He was, on November 25, 1785. Of the jury, Brackenridge tells us only that they voted to convict Mamachtaga without leaving the jury box.

The scene at Hannastown on the morning of December 20, 1785, placed the ambitions and shortcomings of the new state and nation on full display. The setting was outside the courthouse, the first English court west of the Alleghenies, which doubled as a tavern.

On a gallows constructed from rough-hewn logs, Joseph Ross awaited his execution. The twenty-year old Ross, who lived in the area, had been convicted and sentenced to death for buggery – intercourse with a farm animal; the details of his case are almost entirely lost to the unspeakable infamy with which his crime was regarded. His hanging, the last for that crime in American history, proceeded without incident. Because Ross’s crime was committed within the present-day boundaries of Westmoreland County, it is not included in this research.

Mamachtaga then mounted the gallows. His hanging was botched when the rope broke on the first attempt. He was returned to the gallows and hanged a second time. It was the first state execution of an American native and the first murder trial and execution west of the Allegheny Mountains.

Similar circumstances, though with a reversal in the identities of the parties, produced a diametrically opposed process and result a few years later. In the spring of 1791, Captain Samuel Brady, famous for his long service in fighting and killing Native Americans, killed several Native men and women near present-day New Brighton, northwest of Pittsburgh, apparently in retaliation for recent killings of white settlers. He fled and was able to avoid extradition but in 1792 was returned to Pittsburgh for trial at the urging of General Wayne, who was eager for Brady’s return to military service.

In a criminal trial that liberally mixed military and civilian justice in a manner that mitigated Brady’s criminal responsibility and valorized his heroism, the judge directed the jury to consider Brady’s killings acts of war. Under such pressure in a closely watched and celebrated trial, Brady was promptly acquitted despite his confession.