As of this writing (August 2023), Pittsburgh has the peculiar distinction of being the location of the first and last federal death sentences in American history. The first federal death sentences were imposed in the earliest years of American independence, in response to the the killings of federal agents during the Whiskey Rebellion.

The most recent federal death sentence, discussed below, was imposed on Robert Bowers, an avowed White supremacist, who murdered eleven Jewish congregants at the Tree of Life Synagogue, on October 27, 2018.

Whiskey Rebellion Cases

Philip Vigol and John Mitchell

In the first few decades of its existence, during the last few decades of the Eighteenth Century, the geographic boundaries that defined Pittsburgh and the legal authority that secured those boundaries were still being defined. Particularly on the frontier, where the benefits that accrued from stable state authority were less in evidence, claims of federal authority over the citizenry were treated with suspicion. It is these circumstances that led to the Whiskey Rebellion and to the imposition of federal death sentences on Philip Vigol and John Mitchell, the first such sentences imposed in American history and, until 2023, the last such sentences imposed in Allegheny County history.

Tax Resistance as Treason: The Whiskey Rebellion Cases

The costs of fighting the Revolutionary War left the United States government and the governments of the states in significant debt. With new, limited, and largely untested powers of taxation, the federal government faced a critical fiscal challenge. One response devised by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton was a federal excise tax on distilled spirits. Enacted in 1791, that tax was immediately unpopular and widely resisted, particularly along the western frontier of Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Kentucky, which became a state in 1792.

By 1792 and 1793, tax collectors on the frontier were being tarred and feathered, their homes were being burned, and taxes were not being collected. In the spring of 1794, the federal government forced a showdown by issuing subpoenas for tax resisters to appear for trial in Philadelphia; a move that compounded legal jeopardy with a substantial travel burden. When subpoenas were followed in July by writs compelling appearance, the revolt came to a head at the Bower Hill, Allegheny County home of tax collector John Neville, a wealthy planter and slaveholder. Over several days, a number of federal agents and rebels were killed, including Major James McFarlane, before federal forces were forced to withdraw.

For the duration of the summer and into the fall of 1794, the rebels, under the leadership of prominent Washington County elected official, David Bradford, became increasingly radicalized. Talk of organizing a militia, gathering arms, even secession, was heard. Determined to establish federal authority, President Washington ordered the militias of several states to the scene, and then led some of them toward battle. The insurrection collapsed in October 1794.

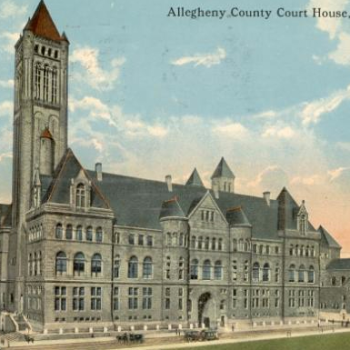

In a powerful initial show of force, fifty-one men faced federal indictments for their roles in the rebellion, thirty-one for treason, with trials to be held in Philadelphia. Quickly tempering that force, only nine of those men were tried for treason and two of them – Philip Vigol (also Weigle and Wigle) and John Mitchell – were convicted and sentenced to death in 1795. Both men were described as simpleminded and neither was a central figure in the rebellion. They were the first people convicted of treason in American history. The German-born Vigol was convicted for a series of violent actions against tax collectors in three counties, including the burning of Neville’s home. Mitchell was convicted for “one continuing act” of treason that included robbing the United States mail, an action he took at the urging of David Bradford, and burning Neville’s home.

Further suggesting the tenuousness of federal authority and the reluctance to assert it fully, President Washington pardoned Vigol and Mitchell on November 14, 1795; the first men to receive presidential pardon in American history. Bradford, who had also been indicted for treason but who fled United States jurisdiction into Louisiana, was pardoned by President Adams in 1799.

After a brief and intense effort to enforce federal and military authority and the newly formed boundaries they protected, even at the cost of life, no additional capital charges for violations of military or federal law have been brought in Allegheny County history. The investment of resources to support and legitimate federal and military authority resulted in fewer challenges to those laws and a broader range of legal responses to those challenges. Though desertions continued until Fort Fayette went out of service after the War of 1812, they were fewer and were not treated as capital offenses. From 1795 forward, the only capital cases brought in Allegheny County were brought under state authority.

Tree of Life Massacre

On the morning of Saturday, October 27, 2018, Robert Gregory Bowers, 46, killed eleven worshippers at the Tree of Life Synagogue in the historically Jewish Pittsburgh neighborhood of Squirrel Hill. Seven other people were injured, including four Pittsburgh Police officers. Bowers was also shot multiple times.

Bowers, a suburban Pittsburgh resident and high school dropout, worked as a trucker. Living alone, he became increasingly radicalized in the on-line White nationalist circles that have proliferated in recent years and have become more violent since the election of Donald Trump. His social media comments reveal disturbing anti-Semitic, anti-immigrant, and anti-Black postings.

The eleven victims, all congregants, were husband and wife Sylvan and Bernice Simon, Joyce Fienberg, Daniel Stein, Melvin Wax, Irving Younger, Jerry Rabinowitz, Rose Mallinger, brothers Cecil and David Rosenthal, and Richard Gottfried.

Arrested at the scene, Bowers was indicted by a federal grand jury on October 31, 2018. After pleading not guilty, he was held without bail. After numerous pretrial motions, Bowers’ trial began in federal court in Pittsburgh on April 30, 2023. In the face of overwhelming evidence, Bowers’ did not offer a defense. He was found guilty of all charges on June 16, 2023.

Focusing instead on trying to forestall the imposition of the death penalty during the penalty phase of his trial, Bowers’ attorneys argued that he had schizophrenia, epilepsy, and serious mental illness; that he had experienced childhood trauma related to his father’s suicide while awaiting trial on rape charges; and that he had been previously institutionalized and had multiple suicide attempts. Bowers was sentenced to death on August 3, 2023.

A long line of appeals is likely. After a flurry of federal executions in the waning days of the Trump administration, the Biden administration has stated its opposition to federal executions and its intention to abolish the federal death penalty. The Department of Justice (DOJ) imposed a moratorium on federal executions in June 2021. At the same time, however, the DOJ has worked actively to oppose many federal death penalty appeals and has pursued two federal capital convictions. Bowers’ death sentence is the first imposed under the Biden administration.