Theodore Paller was part of a large group of Russian immigrants who encountered Alexander Ziatsov in a Chateau St., North Side candy store on April 13, 1919. Ziatsov, a recently discharged US Army combat veteran who had been wounded in battle in France, was in uniform.

Paller, a self-described Bolshevik, and his companions insulted Ziatsov for his service to the United States. Moving to the street, the insults quickly escalated to a fight, which escalated to a shooting when Paller drew a gun. Ziatsov was shot three times, twice in the head. Paller was arrested while running from the scene. Eight others were arrested and held briefly.

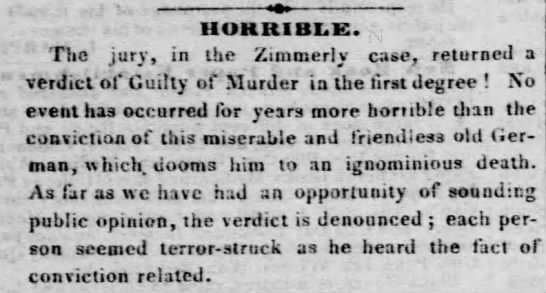

At trial, Paller, a 38-year old steelworker, claimed he acted in self-defense after being attacked by a mob that included Ziatsov. The court permitted testimony from Zaitsov’s cousin, who stated that in his dying declaration, Zaitsov implicated Paller and claimed Paller said at the time “If the Germans didn’t kill you, I will.” He was convicted of first-degree murder on February 3, 1920.

Prior to the formal imposition of his death sentence, Paller filed a routine and rarely successful motion for a new trial, On October 1, 1920, that motion was granted on the strength of new evidence. No surviving record reports that evidence.

Tried again, Paller pleaded guilty and was sentenced to serve 17 to 20 years in Western Penitentiary for second-degree murder on November 16, 1920.

Theodore Paller died of kidney failure in Western Penitentiary on February 7, 1928. He was 47 years old.

Theodore Paller