John Francis Butler was being transported back to Western Penitentiary from a court appearance in Northumberland County when, on May 27, 1959, he shot and killed James R. Lauer, a Northumberland County Sheriff who was transporting him. The driver of the car, Merlin L. Diehl, was threatened with death but was not harmed.

The incident began when Butler, who was in the backseat of the car handcuffed to a belt, was able to escape from the belt and take the gun from the front seat between Lauer and Diehl. Lauer lunged after him. Diehl stopped the car to assist Lauer just as Butler shot Lauer. Diehl and Butler then fled in different directions. Butler ran into the woods, where he hid overnight. He was captured there by police the next morning.

The shooting occurred on Route 19 in McCandless Township, about twelve miles north of Pittsburgh.

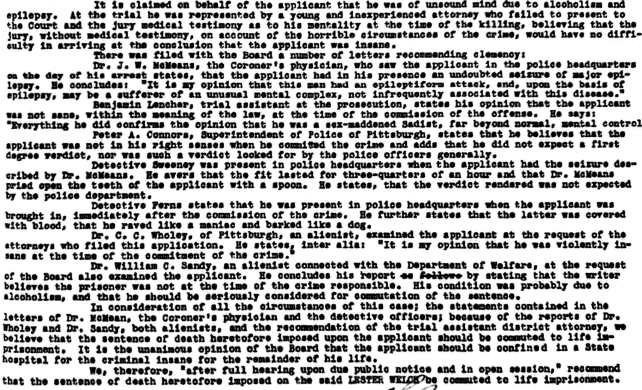

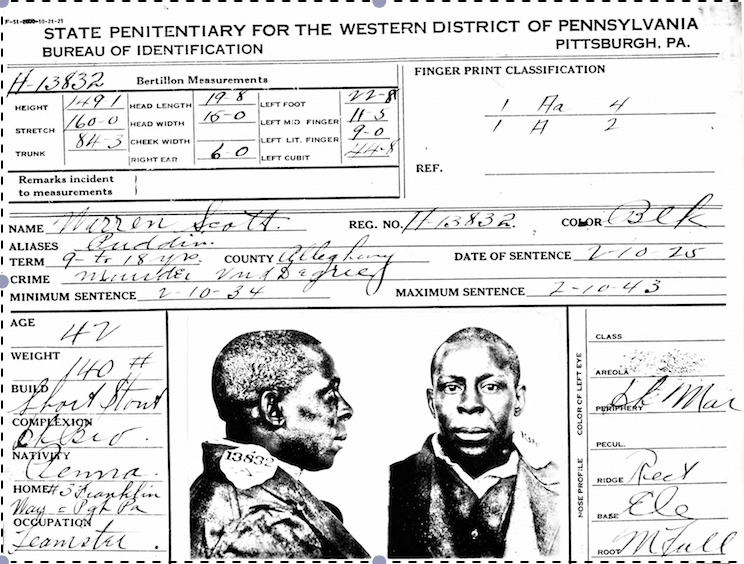

At trial, Butler, a 49-year old Philadelphia native who was serving a four to ten year sentence for a 1958 armed robbery of a group of priests in a monastery and had a lengthy criminal record, mounted an unsuccessful mental health defense.

John Butler was found guilty of first-degree murder on May 20, 1960, and sentenced to death on November 28, 1960.

Though the circumstances of the crime, the identity of the victim, and Butler’s record weighed in favor of his execution, the Civil Rights Movement, the legacy of World War II, and other changes broadly understood as the “evolving standards of decency,” were heightening the legal scrutiny and slowing the pace of death sentencing and executions across the United States.

Indeed, Allegheny County’s final execution had occurred less than two months before Butler killed Lauer. Only a handful of executions would occur statewide over the next seven decades. A national death penalty moratorium was only a few years away.

On appeal, Butler argued that his defense was undermined by the partiality of the psychiatrists who evaluated him and by a series of technical errors in the conduct of the trial. His conviction was “strongly sustained” by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court (Commonwealth v. Butler, 405 Pa. 36, 1961).

Butler appealed that ruling to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals in Philadelphia. While dismissing most of his claims, the court agreed that Butler’s due process rights were violated by the failure of the court to admit evidence suggesting that Diehl and Butler had struggled in the backseat of the car for control of the gun that killed Butler. That testimony, it was stated, might have raised doubt about the degree of murder involved in killing Lauer (Butler v. Maroney, 319 F.2d 622, 1963).

As a result, Butler’s conviction and death sentence were overturned.

With his retrial approaching, Butler pleaded guilty on September 16, 1963. The court then fixed the crime at first-degree murder and sentenced Butler to life imprisonment.

In a response that exemplified the tensions generated by the increasing judicial scrutiny of the criminal justice system, Common Pleas Court Judge Samuel Weiss, who presided at the original trial, attacked the Third Circuit as a “haven of refuge for rapists, cop killers, and armed thugs.”A Pittsburgh Press editorial echoed that sentiment.

John Francis Butler died on May 9, 2000. Merlin Diehl died in 1996.

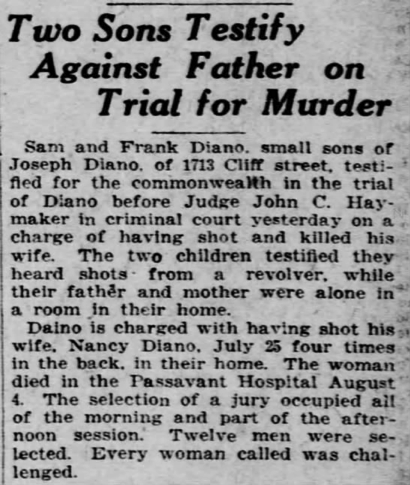

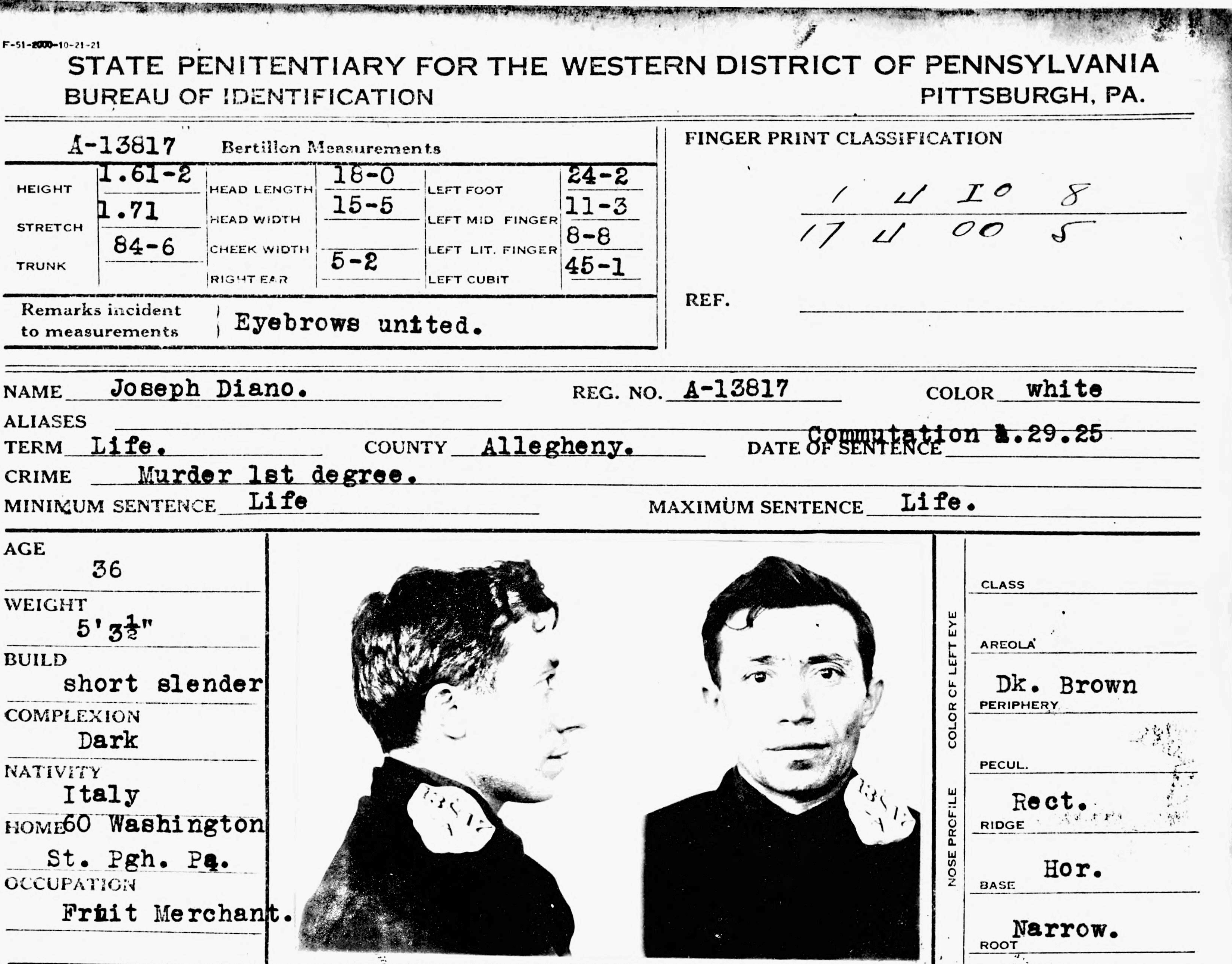

1713 Cliff St.

1713 Cliff St.

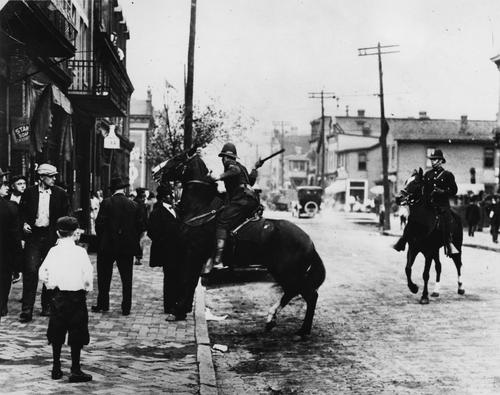

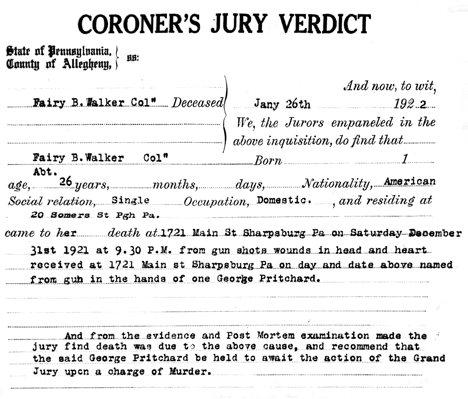

1721 Main St., Sharpsburg today

1721 Main St., Sharpsburg today