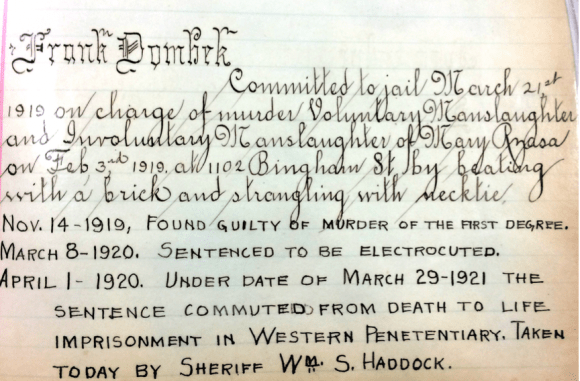

On the morning of February 3, 1919, Frank Dombek went to the Bingham St., South Side home of Jacob and Marie (Latocha) Rzasa, with whom he had previously boarded. All were Polish immigrants.

Finding Marie alone, Dombek demanded all her money. When she refused, he beat her with a brick and strangled her. He then stole several hundred dollars in cash and securities and fled.

The murder occurred in the midst of the effort to enact Prohibition, which Pennsylvania had voted to support the same day as the murder.

That effort was supported by sensationalistic stories of alcohol-fueled immigrant lawlessness. Probably not coincidentally, alcohol figured prominently in the official narrative of Rzasa’s death, though it is not clear that it figured prominently in Dombek’s actions that day.

Dombek, 26, who had a 1911 conviction for burglary, was apprehended more than a month after Rzasa’s killing, on March 8, 1919, in a New Jersey post office. He had gone there to pick up a letter containing the money he needed to return to Pittsburgh to turn himself in.

It was subsequently revealed that not long after the murder, Dombek, overcome by remorse, sought the counsel of a priest and made arrangements to return to Pittsburgh. At his arrest, he immediately confessed.

On the basis of his signed confession, strong witness testimony, and evidence he had used stolen securities to purchase jewelry, Dombek was convicted of first-degree murder on November 14, 1919.

Immediately after Dombek’s conviction, his attorney filed a motion for a new trial alleging that the foreman of the jury was biased against him, that one juror had misrepresented himself in being seated as a juror, and other improprieties. That motion was rejected and Dombek was sentenced to death on March 8, 1920.

Dombek then appealed his conviction, raising the same issues about juror misconduct. His conviction was affirmed in an unusual single paragraph decision (Commonwealth v. Dombek, 268 Pa. 262, 1920).

Members of the jury supported and advocated for Dombek’s commutation, which was granted on March 29, 1921. In its recommendation, the Pardon Board went so far as to suggest Dombek may not have been responsible for Rsaza’s death.

Dombek was transferred to Western Penitentiary, from which he was paroled in 1933.

From the Allegheny County Jail Murder Book, courtesy of Ed Urban

Claiming he had been coerced into confessing to a crime he did not commit, Dombek sought a full pardon. His request was granted on July 18, 1940.

Once released, Frank Dombek returned to Chicago, where he had lived before moving to Pittsburgh. He died there on September 25, 1984, at the age of 89.

Jacob Rzasa died in Pittsburgh in 1958.