Dennis and Bridget (Skahill) Cloonan, long-married, with four sons, and in their 50s, lived at 52 Congress St. in the Lower Hill District.

They quarreled frequently, though reports indicated that their unhappiness did not involve violence. An apparent source of tension was a property Bridget had purchased in her own name and had refused to co-title with her husband.

Then, on March 17, 1892, St. Patrick’s Day, the Irish-immigrant Cloonan returned from work at the Pennsylvania Railroad, intoxicated, ate the dinner his wife had prepared, and brutally beat her with a chair. He then went to the neighbor’s home and told her to go to his house to see what had happened. There he told a witness that he had suffered long enough and was not going to suffer any more.

Police were summoned and Cloonan was arrested as he walked away from the scene. He confessed immediately and asked the arresting officer to shoot him. After a brief trial, Cloonan was convicted on June 4, 1892, and sentenced to death. He showed little interest in his trial, conviction, or execution.

Police were summoned and Cloonan was arrested as he walked away from the scene. He confessed immediately and asked the arresting officer to shoot him. After a brief trial, Cloonan was convicted on June 4, 1892, and sentenced to death. He showed little interest in his trial, conviction, or execution.

After an unsuccessful appeal, a surprisingly vigorous clemency campaign was mounted, portraying Cloonan as a particularly pitiful and benign character; “a simple minded ignorant, illiterate man, faithful, industrious and kindly in the discharge of his laborious duties…always kind, obedient and faithful.”

Despite hundreds of signatures of support obtained from his Hill District neighbors, Dennis Cloonan’s clemency request was rejected and he was hanged on April 4, 1893.

Cloonan’s was the first execution in Pittsburgh after the Homestead Riot. Inasmuch as Homestead represented the defeat of labor unionism and helped to usher in an era of mass production, it may be used to mark the beginning of the peak industrial era in Pittsburgh that lasted until the steel industry began to move closer to the resource deposits and shipping routes along the Great Lakes after 1920.

During this era, Pennsylvania – not Virginia or Georgia or Texas – was the nation’s leading executioner; a result of the migration, immigration, urbanization, and associated racial and ethnic tensions of industrialization.

Congress St. today; a post-industrial landscape

Congress St. today; a post-industrial landscape

New York Times, October 5, 1883

New York Times, October 5, 1883

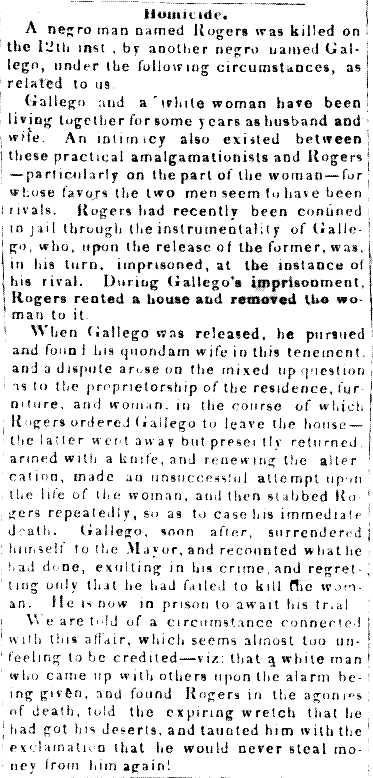

Public Ledger (Philadelphia), December 21, 1837

Public Ledger (Philadelphia), December 21, 1837