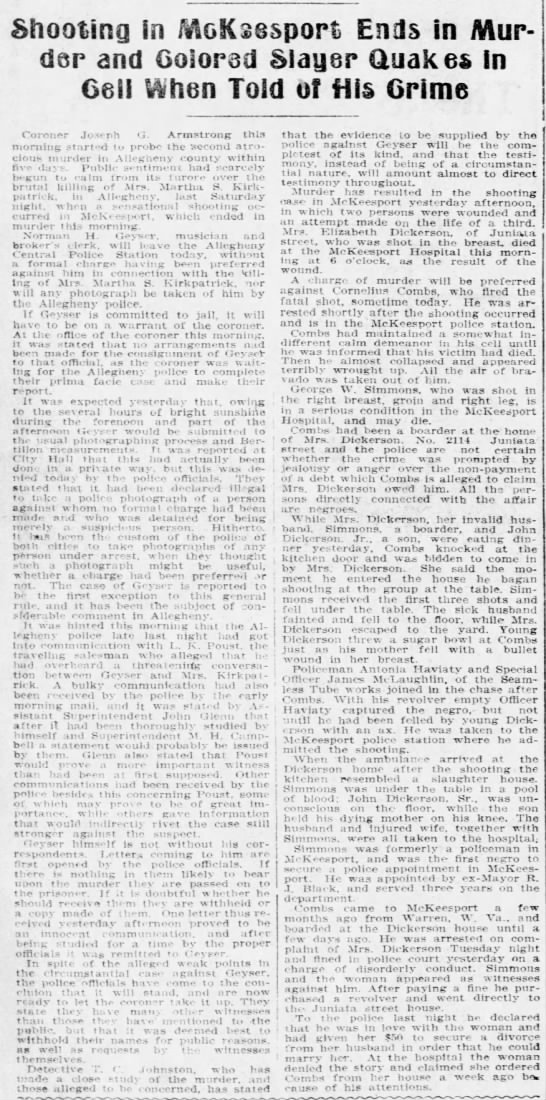

In a case that resembles the Werling case of a decade earlier in its documented history of serious and serial domestic violence and inadequate official concern for that violence, Cornelius Combs shot Mrs. Mary Elizabeth (Lizzie) Dickerson, his former landlady, in her McKeesport home on February 8, 1905. Dickerson died the following morning.

This final incident in a long-running series of threats and assaults began when Combs walked into the Dickerson home at 11:30am and began shooting without warning. He shot and wounded Dickerson and George Simmons, a police officer and boarder in the home at the time. Both victims fled to the cellar; Combs followed and continued shooting.

Dickerson fled the house. Combs followed, caught her in the street, and fired the fatal shot. He was apprehended while fleeing and promptly confessed to police.

Combs, who began boarding at the Dickerson home after moving from West Virginia, had grown infatuated with Mrs. Dickerson. Over the previous months, he had harassed, sexually assaulted, and injured her. In several of those incidents, he was forcibly removed from the premises by police.

Most recently, Dickerson had Combs arrested on February 7, the day before her murder. He was fined for disorderly conduct and released from jail the next day. He promptly obtained a gun and returned to Dickerson’s home to kill her.

With his confession and the eyewitness testimony of several witnesses, Combs was convicted on September 29, 1905. His defense of intoxication failed.

His request for a new trial was rejected and he was sentenced to death on December 1, 1905. John Dickerson, Lizzie Dickerson’s husband, who was in the home at the time of her killing, died on December 8; his death from edema was said to have been hastened by the trauma of the murder.

On appeal, Combs argued that the case was properly second degree murder. That claim was rejected (Commonwealth v. Combs, 216 Pa. 81, 1906) by reference to trial evidence of premeditation and deliberation.

Cornelius Combs was executed on September 6, 1906, the same day as John Williams. They were the first men to be executed on the county’s new steel scaffold.

At the time of his execution, the Pittsburgh Press noted that Combs “alone in the world, had been living a loose life about McKeesport for some time.” He is reported to have approached his execution with little concern.

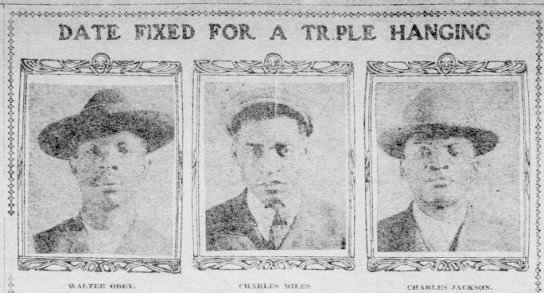

Pittsburgh Press, March 13, 1903

Pittsburgh Press, March 13, 1903 Pittsburgh Press, February 2, 1904

Pittsburgh Press, February 2, 1904

The view from Pius St.

The view from Pius St.

Chanosky’s was the first case since

Chanosky’s was the first case since