The mill towns of Braddock and Homestead, on opposing sides of the Monongahela River, were the center of the Pittsburgh steel industry when Pittsburgh was at the center of the steel world. Though Homestead would come to represent the violent struggle for the dignity of steelworkers during the epic clash between striking workers and Carnegie Steel that occurred there in July 1892, Braddock’s Edgar Thomson Works, the largest jewel in Carnegie’s crown, operated through the same volatile mixture of class and ethnic tensions.

Though Carnegie viewed the Edgar Thomson Works as a tribute to the Social Darwinist ideology of his “master,” Herbert Spencer, a place where the natural order dictated workplace relations, a much more exploitive reality prevailed. That reality was on full display on January 1, 1891, when already agitated workers, mostly recently-arrived Hungarian and Slavic immigrants, clashed with native born Western European management and supervisory personnel about working on New Year’s Day.

Michael Quinn, an Irish immigrant supervisor, was badly beaten during those clashes. He died on January 5; his cause of death was listed as a fractured skull.

Mass arrests followed the riots and the killing, cheered on by newspaper accounts of “semi-civilized Slavs.” Ultimately, dozens of defendants were tried for rioting.

Andrew Toth, Michael Sabol, and George Rusnok, all Hungarian-born steelworkers among the hundreds there that day, were arrested for Quinn’s murder.

Foreshadowing the Homestead Strike and the stark reversal of fortunes it represented for labor as well as the changing face of labor in industry, the three men were the first Eastern Europeans involved in a capital murder case in Pittsburgh’s history. There would soon be many others.

Toth, Sabol, and Rusnok were indicted on January 15, 1891, well before passions could cool. At trial in February 1891, held amidst stories of “riotous Huns,” socialists and anarchists, and nascent revolution, some witnesses testified that Toth administered the fatal injuries. Others testified that Sabol and Rusnok were involved and that Toth was not. Still others offered accounts that did not involve the three defendants.

Despite the conflicting testimony and a defense that drew attention to the rampant prejudice of the time and the trial, all three were convicted on February 7, 1891, on the thinnest of evidence, and sentenced to death on April 8, 1891. The twelve men sitting in judgment of them were, as far as I can determine, exclusively Pennsylvania-born of Western European ancestry.

On appeal, the court affirmed the first-degree murder convictions of each defendant on June 5, 1891 (Commonwealth v. Andrew Toth et al, 145 Pa. 308, 1891). In ruling that, despite the melee preceding Quinn’s beating and the confusion it created, the evidence was sufficient to sustain three first-degree murder convictions, the court stated “if there ever was a time in the history of this state when such a principle [of liability attached to a ‘common riotous purpose’] should be enforced it is now.”

The three hastily imposed death sentences were followed by regrets, recriminations, and, after protests across the country and a massive national and international clemency campaign, reprieves.

Away from the growing labor tensions in the Monongahela Valley, Governor Pattison commuted their death sentences to life imprisonment on February 2, 1892. At the time of their release from death row, the Post-Gazette referred to Toth, Sabol, and Rusnok as “very happy murderers.”

The conflicting trial testimony and the very different descriptions of what happened during the riot were the justification for the commutations. The high level of public passion about the case was also a factor. Even Andrew Carnegie and his lieutenant, Charles Schwab are reported to have favored the commutations.

Pardon campaigns followed. Included were petitions containing thousands of signatures from Hungarian and Slavic groups around the country, as well as from Braddock and Homestead. Also included were letters of support from the mayor of Pittsburgh; the Allegheny County Commissioner, Controller, Prothonotary, and Coroner; the Police Chief and the Justice of the Peace of Braddock, who wrote that “Rusnok and the other two defendants were litterly (sic) railroaded through the courts to conviction and it was not till it was too late that people came to their senses. Now it is hard to find a single person in the town of Braddock familiar with the facts of this case who does not believe that Rusnok should not have been convicted;” the editor of the Pittsburgh Press; and religious leaders. Their letters emphasized the discrimination and rush to judgment in the arrests, trials, and convictions.

In March 1895, Sabol was pardoned and released from prison. Rusnok’s pardon followed in October 1897. Both men remained in Braddock and resumed the lives that had been interrupted.

Sabol, 25 years old at the time of Quinn’s death, married in 1899 and started a family. He died in Braddock in 1920. Rusnok, 22 at the time of Quinn’s death, married in 1898, and started a family. He and his family returned to Trebisov, Hungary (now Slovakia), the town of his birth, in 1903. He died there in 1916.

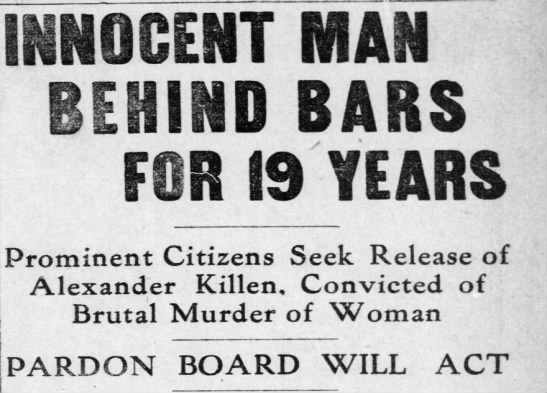

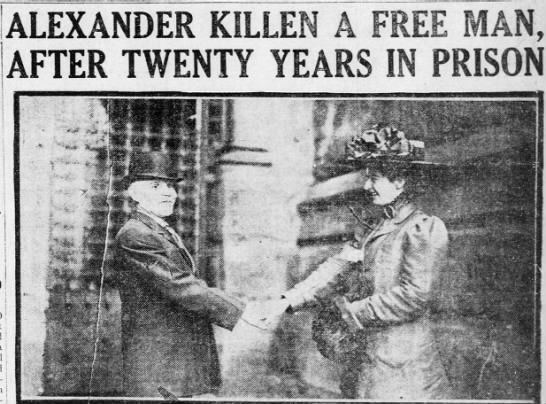

Efforts to have Toth pardoned were unsuccessful for more than a decade. Finally, on March 15, 1911, the state Board of Pardons recommended his pardon and he was released from prison.

Efforts to provide him some financial compensation for his wrongful imprisonment were unsuccessful. “Broken and crushed” (Pittsburgh Daily Post, August 2, 1911), he returned to Hungary in August 1911.

At the time of his release, the Pittsburgh Press, hardly sympathetic toward the cause of labor, referred to him as “innocent almost beyond a doubt” and “a modern Monte Cristo in servitude and sufferings.”

It was likely Steve Toth, a fellow steelworker but reportedly no relation to Andrew, committed the murder. He is said to have confessed from his deathbed in 1911, after he too returned to Hungary.

In his pioneering research on wrongful convictions, Yale law professor Edwin Borchard included Toth, Sabol, and Rusnock case in his 1932 book Convicting the Innocent.

Pittsburgh Press, April 24, 1909

Pittsburgh Press, April 24, 1909

Newspaper reports portrayed each man favorably, finding little of concern in the violence between them or in the violence in their backgrounds. Abernathy, nicknamed “Bloody,” was twenty-two years old and unemployed, with a prior conviction for disturbing the peace and reportedly unable to hold a steady job due to unreliability and troublemaking.

Newspaper reports portrayed each man favorably, finding little of concern in the violence between them or in the violence in their backgrounds. Abernathy, nicknamed “Bloody,” was twenty-two years old and unemployed, with a prior conviction for disturbing the peace and reportedly unable to hold a steady job due to unreliability and troublemaking.

Pittsburgh Daily Post, April 27, 1888

Pittsburgh Daily Post, April 27, 1888