When 19-year old Robert Stoner drove past his uncle’s home on the evening of March 4, 1948, the lights were on. Knowing the Broughton Rd., Bethel Township home should have been dark – Raymond and Elsie Klinzing were vacationing in Florida – the alert Stoner stopped, saw men in the home, and called police from a neighbor’s home.

When police responded to the scene, they found Edward DiPofi and John Regis Wilson in the home and arrested them. While handcuffed and being escorted to a police car, DiPofi used a gun concealed in his waistband to shoot Officer Joseph Chmelynski and his partner, George Kercher. DiPofi and Wilson fled.

Police set a trap for DiPofi at his home later that evening. When two men approached the home, police opened fire with a submachine gun. The two men – a police officer and a passerby – were wounded. DiPofi was not there.

DiPofi and Wilson were apprehended the morning after the killing, in New Eagle, Pennsylvania, after police were alerted by a suspicious taxi driver. The arrest occurred as the taxi arrived at DiPofi’s mother’s home.

Chmelynski died of his wounds on March 9, 1948. Kercher, who had been shot in the stomach, recovered.

Edward DiPofi was a World War II Army veteran from East Liberty. John Regis Wilson was his brother-in-law. They were part of a network of burglars active in the southern suburbs of Pittsburgh.

As they awaited trial for murder, DiPofi and Wilson were among a group of ten men who pleaded guilty to unrelated burglary and larceny charges. DiPofi was sentenced to 15 to 30 years on those charges. Wilson was sentenced to 20 to 40 years in prison. The gun later used to kill Chmelynski was among the items stolen by DiPofi.

At trial for Chmelynski’s murder, DiPofi was confronted by eyewitnesses that included Officer Kercher. He was convicted of first-degree murder on June 12, 1948 by a jury that included seven women and five men. After his motion for a new trial rejected, he was sentenced to death on September 29.

After a delay to allow the passions of potential jurors to calm, Wilson made a last minute decision to plead guilty to murder in September. John Regis Wilson was sentenced to life imprisonment on September 14, 1948. He died on May 23, 1958.

DiPofi’s appeal, which claimed prosecutors prejudiced the jury through the introduction of evidence related to fifteen previous crimes, was rejected (Commonwealth v. DiPofi, 362 Pa. 229, 1949) in favor of the state’s strained contention that knowledge of those convictions was used by the jury only in weighing sentence. Justice Jones filed a sharply worded dissent.

DiPofi’s appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was rejected.

Despite the heinousness of the crime and the strength of the case against him, a significant clemency effort was mounted on DiPofi’s behalf, involving churches, Italian organizations, and others. Central to that effort was a psychological evaluation that characterized DiPofi as a “psychoneurotic with hysteria,” that indicated he was a combat veteran of World War II who had received mental health treatment during his military service, and that he had experienced multiple traumatic head injuries as a child. This information, the report indicated, was unknown to the defense at trial.

Edward DiPofi’s clemency request was rejected on December 21, 1949, and he was executed on January 9, 1950.

DiPofi was the last white person from Allegheny County to be executed and only the second white person, along with Martin Sullivan, to be executed since 1930. Eleven Black men were executed during that period.

George Kercher became chief of police of Bethel Township. After being removed from that position by a newly elected board in 1951, a firing that he contested unsuccessfully, he was appointed to a position as a county detective. He died in 1954; never having fully recovered from the wounds inflicted by DiPofi. He was 47.

Pittsburgh Press, February 26, 1939

Pittsburgh Press, February 26, 1939

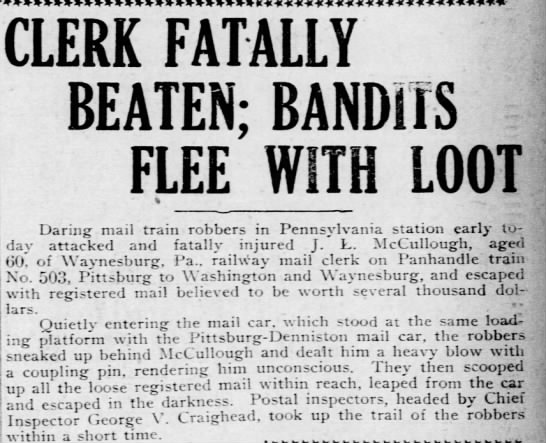

The lead headline, ahead of national and international stories, April 20, 1921

The lead headline, ahead of national and international stories, April 20, 1921

It’s a case that both flaunts and implicates the racial and sexual taboos so prominent at the time and baffles contemporary readers for the utter absence of any coherent narrative as to what happened.

It’s a case that both flaunts and implicates the racial and sexual taboos so prominent at the time and baffles contemporary readers for the utter absence of any coherent narrative as to what happened.