Walter Troy lived in a two-room house on Rowley St. in the Hill District with his wife, Marie W. (Ronezka), their four children, and his mother, Emma Condon.

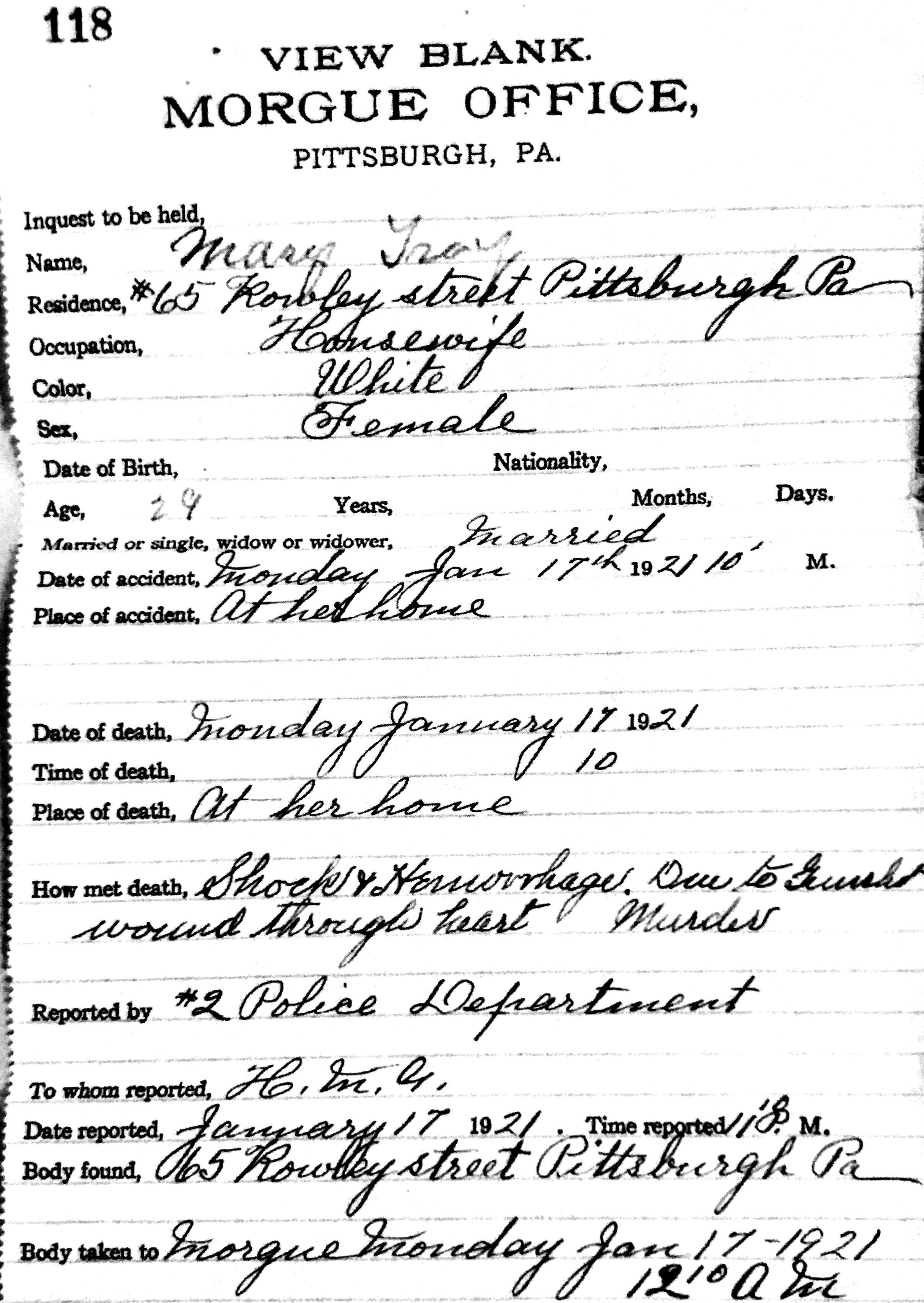

On January 17, 1921, not long after losing his job as a Pennsylvania Railroad police officer, Troy came home drunk, quarreled with his pregnant wife, and shot her.

Amidst the shooting, Condon fled to the Webster Avenue home of her daughter and son-in law, Mary and Edward Zahn. Troy and his oldest son, Albert, soon followed. There Troy washed off evidence of the crime and developed a plan to blame nine-year old Albert for the shooting, apparently threatening him to tell police he accidentally shot his mother.

Responding to the shots, police went to the Troy home, found the Zahns there investigating the scene, and soon arrested Troy. Albert Troy initially told police that he had accidentally shot his mother. Under questioning, he changed his story and implicated his father.

Earlier that day, Troy had spoken with his mother to make sure his wife had made payments on their life insurance policies.

At trial, the prosecution offered the testimony of Troy’s son and mother. In his defense, Troy claimed he was drunk at the time of the killing. He was convicted of first-degree murder on December 14, 1921, and sentenced to death on February 17, 1922.

While pursuing post-conviction relief, Troy and fellow capital defendants John Rush and Joseph Thomas were involved in an escape plot. The plot was foiled when a gun was found in Rush’s cell. Under questioning, Troy revealed the plans to jail authorities.

Troy’s conviction was affirmed on appeal (Commonwealth v. Troy, 274 Pa. 265, 1922) when his challenge to the competency of his young son’s testimony was rejected.

Despite his escape plans and the strength of his conviction, Troy was granted several respites to consider his clemency petition before that petition was rejected on November 22, 1922.

Walter C. Troy was taken to Rockview and executed on December 4, 1922. Long-time warden John McNeil, who worked in the jail for 39 years, later said Troy took his execution harder than any other inmate he had known.

Rowley Street today

Rowley Street today

Emma Condon died in Pittsburgh in 1932. Albert Troy died after a fall in his Butler home in 1963.

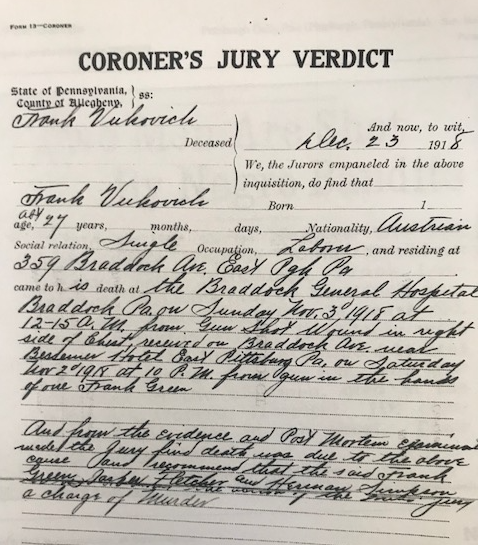

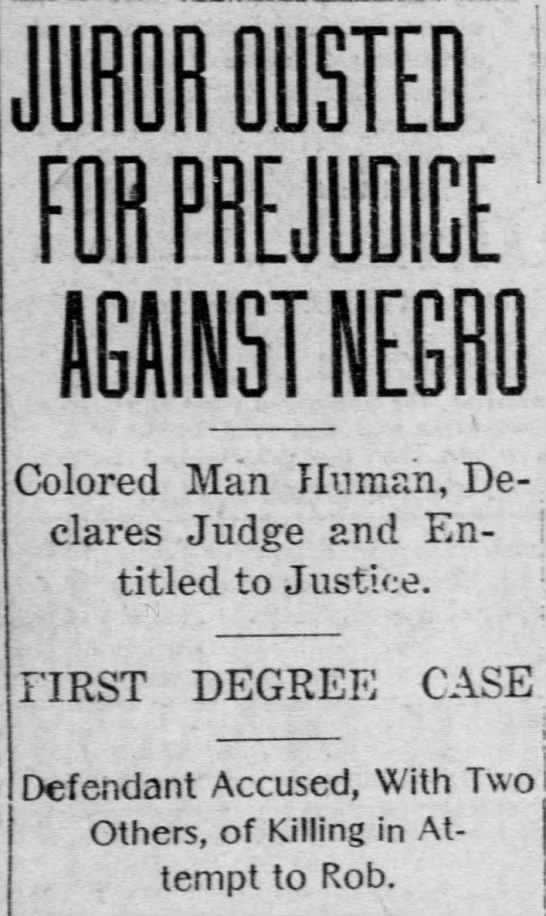

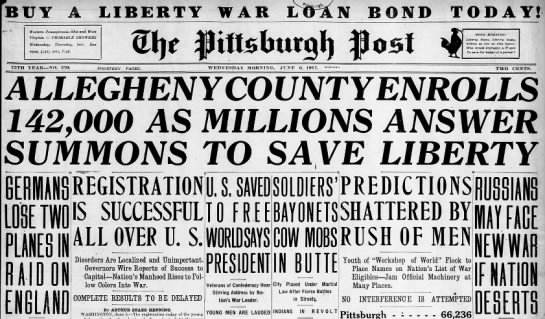

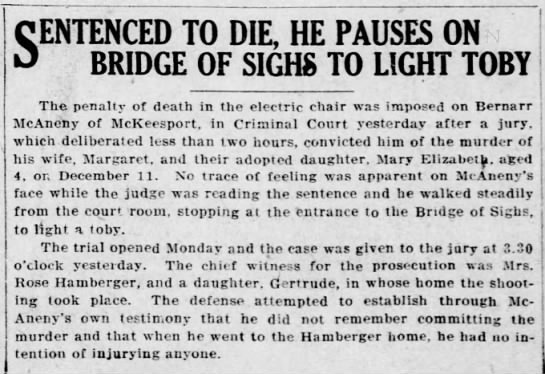

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 22, 1921

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 22, 1921

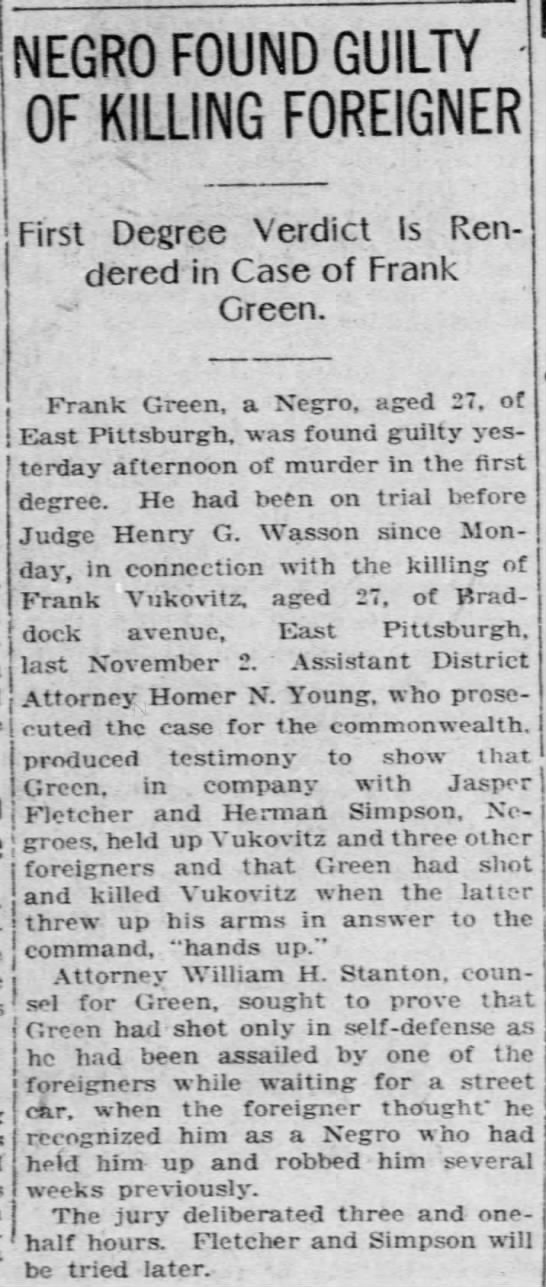

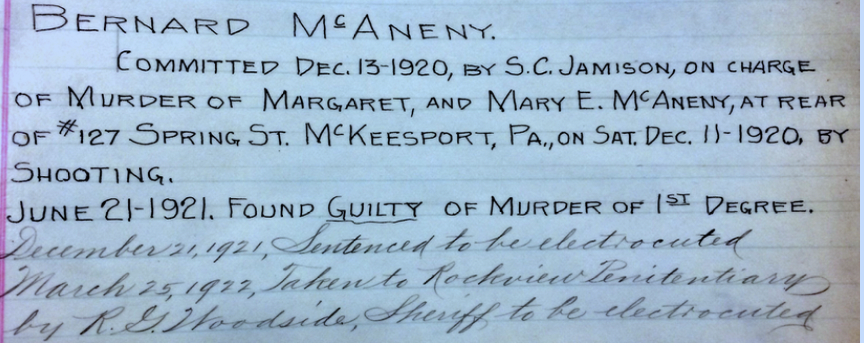

Pittsburgh Press, October 23, 1921

Pittsburgh Press, October 23, 1921