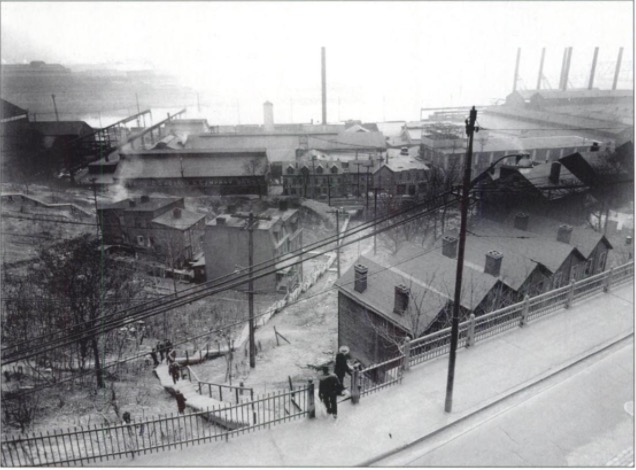

After exiting the trolley at Fifth Avenue and the Maurice St. steps in Oakland late on the evening of September 22, 1900, Peter Hoban, a Pittsburgh-born steelworker, and his friends encountered George Christian and John Hastings. Hoban’s party was returning from work at the Homestead mill.

Much like the Frank Green case two decades later, reports of what happened next vary widely. Hoban’s friends said that Christian and a group of Black men blocked the path of Hoban’s group and pushed them when they tried to pass. Christian claimed Hoban and his friends were the aggressors, pushing the men and hurling racial epithets. Whichever the case, Hoban was shot. He died early the next morning.

Christian fled, traveling to Baltimore and Washington, before going to New York City. He was arrested there on December 5, 1900.

At trial, the prosecution advanced an unlikely story of white innocence and Black aggressiveness. Christian’s defense argued that Hoban and his friends were the aggressors, leading Christian, an obviously proud and self-possessed man, to draw a gun and shoot Hoban once in the chest.

With the racial dynamics certainly favoring the state’s case, Christian was convicted of first-degree murder on January 5, 1901. His motion for a new trial was rejected and he was sentenced to death on February 28, 1901.

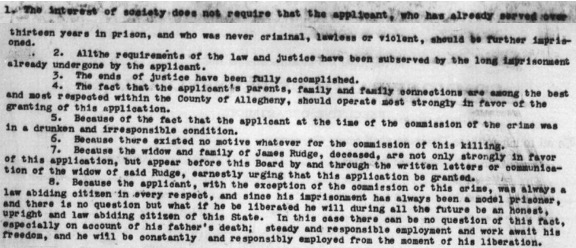

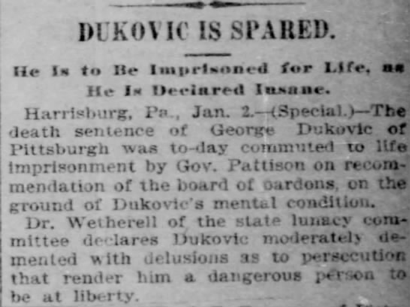

After a Pardon Board recommendation, Christian’s death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by Governor Stone on November 13, 1901, due to questions about the appropriate degree of murder. The same dilemma had faced Christian’s trial jury.

At the time of his release, The Pittsburgh Press published a full-page story of Christian’s life and crimes. Lacking the customary racist tropes of the era, the story is remarkable for the interest and respect it displays for the twice-convicted murderer.

Transferred to Western Penitentiary, on October 1, 1904, Christian was involved in the non-fatal stabbing of fellow inmate Charles Jones. Jones was targeted in retaliation for telling prison authorities of an escape plan that included Christian; famed anarchist and attempted killer of Henry Clay Frick, Alexander Berkman; Biddle brothers accomplice, Walter Dorman; and other notorious inmates. Berkman’s previous escape plan, in 1900, had likewise been foiled.

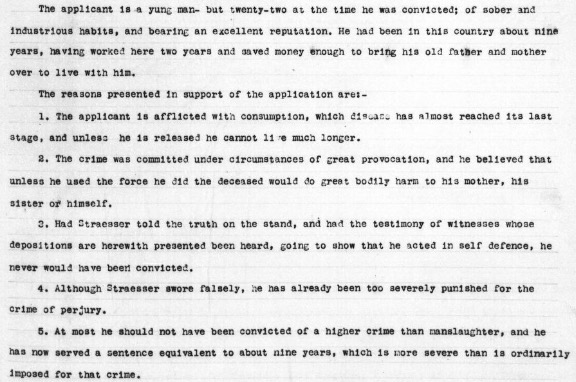

George Christian was placed in solitary confinement, where he died of tuberculosis on December 5, 1906.

Prior to moving to Pittsburgh, Christian, who was born into slavery in Virginia around 1850, had been sentenced to life imprisonment for killing a man in West Virginia. During the gubernatorial race in 1889, a campaign event Christian helped organize in the Black community was attacked by white residents. Christian was among those arrested and held in a make-shift jail. When the jail was set on fire, Christian escaped, only to be later arrested and convicted of murder for having pushed another man into the fire.

He was pardoned by Governor Atkinson, who was allied with the candidate Christian had been supporting, in April 1900, after serving eight years (the official account of the pardon tells a very different story in which Christian is illiterate and dissolute and an object of pity). Stories circulated of a much darker relationship, in which Christian was a political assassin pardoned to protect him from retaliation.