James Kelly, Daniel Denny, and John Richards, all single men working as glassblowers, probably at the Aetna Glass Works, went out drinking in their Lawrenceville neighborhood on October 7, 1857. After stopping at a few taverns, Kelly suggested that they go to the nearby home of Wilhelmina Weissman, whom Kelly described as a prostitute.

Weissman lived with her elderly father, Henry, in a dilapidated home on the estate of Philip Winebiddle, a wealthy landowner who allowed the Weissmans to live free of charge.

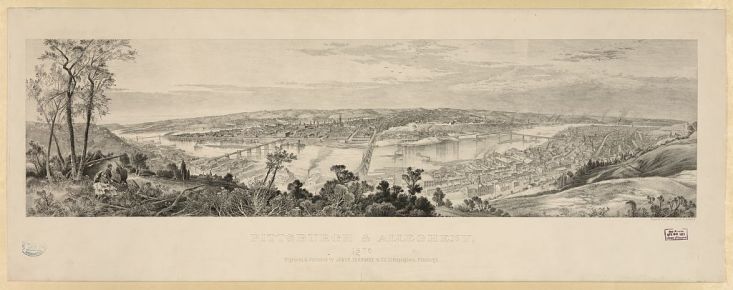

Scion of a prominent founding family with significant landholdings in East Pittsburgh, as a young man Philip Winebiddle killed an unnamed enslaved man and fled efforts to arrest him. He was later tried for murder and “acquitted after a tedious trial of fifteen hours.”

Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, November 19, 1816

Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, November 19, 1816

When no one answered the door at the Weissman residence that evening, Kelly, Denny, and Richards let themselves in and went to the bedroom where Wilhelmina and Henry slept. Awakened by the intruders, Henry fought the men while Wilhelmina ran for help. When she returned, she found her father had been seriously injured. Henry Weissman died the next day. Richards, Denny, and Kelly were arrested on October 8.

Kelly, 20-years old and single, was tried first; his trial began on January 12, 1858. At trial, he claimed that Weissman was a prostitute he had patronized previously and that he and his friends were merely interested customers when they were forced to defend themselves.

After a defense that emphasized Wilhelmina Weissman’s bad character and sexual immorality (including claims that she was pregnant, unmarried, and syphlitic), Kelly was convicted of first-degree murder on January 16. After his motion for a new trial was rejected, he was sentenced to death on March 9, 1858. Denny was convicted of manslaughter and Richards was acquitted.

At the time of Kelly’s original trial, Fife, Jones, Stewart, and Lutz were awaiting execution. The Pittsburgh Gazette of January 18, 1858, wrote “Our jail has never presented such a spectacle to the eyes of the world as at present and we trust it never may present such an one again.” On the same day, the Daily Post wrote “We blush to record the dreadful tragedies for which the community now stands resposible (sic). Fife, Charlotte Jones, Stewart, Lutz and Kelly, with the dismal prospects of others being added to the column. We have no heart to enter upon the discussion of the causes of this fearful increase of the devilish spirit of murder; neither do we desire to reiterate the horrible details of this terrible result. It is enough to contemplate that cold-blooded murder – a total disregard of the value of human life, has been considered a trifle in this region, by bullies and street corner ruffians.”

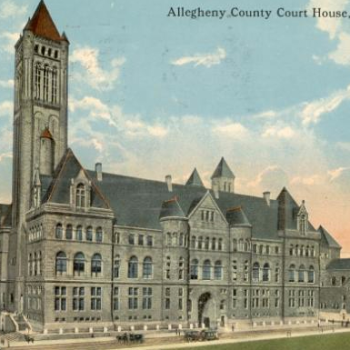

On appeal, on July 15, 1858, Kelly’s conviction was reversed and he was granted a new trial (Kelly v. Commonwealth, 1 Grant 484, 1858). The reversal was granted due to the court’s concern that the circumstances of the offense mitigated Kelly’s premeditation, raised the issue of self-defense, and, in the absence of a clear intent to rape, did not rise to the level of first-degree murder. Specifically, Kelly had been charged with felony (rape) murder, yet his intent to rape had not been established and could not be used as a component of the charge if Wilhelmina had fled before the killing occurred.

Kelly’s second trial began on November 30, 1858. He was convicted of second-degree murder on December 2, 1858, and sentenced to eight years and nine months in Western Penitentiary.* After serving all of that sentence, Kelly was discharged on September 2, 1867. He died in Pittsburgh in 1914.

Wilhelmina Weissman died in Allegheny General Hospital on May 8, 1899.

* Kelly was the first death-sentenced defendant to serve time in Western Penitentiary. By the time he arrived, the famed Western Pen, a once-promising testimony to the failed belief that prisons could serve as beacons of “moral architecture,” was already on its second (of three) iterations. The idealism surrounding prisons at the time was one reason that the death penalty was not used more frequently. That most murderers were young white men of Northern and Western European ancestry was another important moderating factor. Only two (Jewell and Fitzpatrick) of the thirteen (Honeyman, Moode, Dunn, Lutz, Kelly, Keenan, Lynch, Murray, Meyers, Linkner, Abernathy) white men sentenced to death for fatal assaults involving white victims before the late 1800s were executed. Sounding this note, the Pittsburgh Daily Post in 1858 also wrote that “the humanity of the age forbids [making] the laws more stringent” before concluding that “the best defense is not punishment but prevention.” As the profile of the offender changing later in the century, use of the death penalty increases accordingly.

Police were summoned and Cloonan was arrested as he walked away from the scene. He confessed immediately and asked the arresting officer to shoot him. After a brief trial, Cloonan was convicted on June 4, 1892, and sentenced to death. He showed little interest in his trial, conviction, or execution.

Police were summoned and Cloonan was arrested as he walked away from the scene. He confessed immediately and asked the arresting officer to shoot him. After a brief trial, Cloonan was convicted on June 4, 1892, and sentenced to death. He showed little interest in his trial, conviction, or execution.

Congress St. today; a post-industrial landscape

Congress St. today; a post-industrial landscape

New York Times, October 5, 1883

New York Times, October 5, 1883